INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the rising popularity of e-cigarettes has sparked the need for more research on the health impacts of vaping. In 2022, 20% of Canadian young adults aged 20–24 years reported having vaped in the past 30 days, which is up from 17% in 2021 and 13% in 20201. Those aged ≥25 years were less likely to have vaped in the past 30 days, given that only 15% people of this age group reported ever using e-cigarettes in their lifetime1. With an expanding market and rising prevalence of e-cigarette use among young people, understanding the potential risk is crucial.

E-cigarettes have been found to deliver fine and ultrafine particles in flavored e-liquid, and trace metals from the heated coil into the lungs2-6. These toxicants, in addition to the nicotine component, have potentially damaging effects on the respiratory system5,7. In recent years, several reviews have been published which showed that e-cigarette use might increase risk of several respiratory conditions including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and pulmonary inflammation2,5,8,9. However, these reviews were often limited by lack of meta-analysis, focusing on a specific type of study design, biomarkers, or toxicological analysis of e-cigarette contents. As the research on the health effects of vaping are rapidly emerging, there is a need for conducting an updated review. Our review sought to amalgamate the available evidence to provide insights into both the immediate and long-term impacts of e-cigarette exposure on respiratory health. The research question for our review was: ‘Does nicotine e-cigarette or vaping product use (active and passive/second hand use) impact respiratory health?’. We also explored whether these impacts varied in magnitude by different population subgroups by vaping and smoking status and sociodemographic conditions such as age groups, sex, gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, indigenous identity, pregnant/postpartum, education level, individual or household income, employment status, and occupation.

METHODS

This review was conducted as a part of the ‘Vaping and Electronic Cigarette Toxicity Overview and Recommendations (VECTOR)’ project aimed to evaluate various health risks (i.e. cardiovascular, respiratory, cancer, dependence) of vaping e-cigarettes in different population groups based on their vaping and smoking status10-12. The protocol of this project was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023385632) and we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline13 and guideline for reporting animal evidence14.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched the following databases: CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed and Cochrane library. As the National Academics of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine review, 20183 and the McNeill et al.2 review included studies on respiratory health effects of e-cigarette use published since the inception of the databases up to June 2021, we limited our search for studies published between July 2021 and December 2023 to avoid duplication with those reviews. The literature search was conducted under the VECTOR project with an initial search done in 31 January 2023 and updating it in 2 January 2024. The detail database search strategies are presented as Supplementary file Material 1. The McNeill et al.2 review did not conduct any sociodemographic factor-based subgroup analysis, so we reviewed the 427 original studies that were included in that review to assess their eligibility for subgroup analysis. We did not conduct any manual or grey literature search for this review.

Eligibility and study selection process

We included studies based on following inclusion criteria: 1) population – human, animal, and cell/in vitro (i.e. human or animal); 2) intervention/exposure – exposed to nicotine e-cigarettes (active or second hand); 3) comparators – exposed to either cigarettes, other tobacco products, cannabis vaping products, placebo or no exposure; 4) outcomes – any respiratory health effects; and 5) study designs – any peer-reviewed studies including observational and experimental studies except qualitative studies and literature reviews. Additional criteria were studies published in English or French language due to our expertise in these two languages and availability of most of the publications in English language. We excluded studies evaluating respiratory health effects resulting from cannabis vaping, heated tobacco products or other tobacco products use. As we have assessed risk of cancer separately in the VECTOR project, we excluded studies on lung cancer from this review, but stated the findings on lung cancer in another article10. Similarly studies on other health effects of e-cigarette use (i.e. cardiovascular, other cancers, vaping dependence)10-12 were excluded as part of the VECTOR project during the full-text screening process.

All search results collected from the electronic databases were imported to the Covidence workflow platform where duplicate articles were removed automatically. We also removed any duplicate articles which were missed by Covidence manually. Study selection process was conducted in the Covidence and full texts of each articles following title and abstract screening were uploaded there. At least two reviewers independently screened each title and abstract followed by full text reviews of the remaining articles in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by one reviewer upon discussion with or guidance from other reviewers.

Data extraction and management

A custom-made data extraction form was developed which mainly included general characteristics of the included studies (author and year, funding source, conflict of interest), population characteristics (sample size and demographics), type and duration of exposure, intervention/exposure characteristics (definition and sample size of comparison groups), health condition/outcome assessed, reversibility of health effects, study findings, subgroup types, sample size of the subgroups and findings, and risk of bias ratings for each study. While one reviewer conducted the data extraction, another reviewer checked for accuracy of the extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the reviewers. In accordance with the McNeill et al.2 review, we assessed the health effects of 3 different types of e-cigarette exposure: acute (one-off exposure to 7 days), short- to medium-term (8 days to 12 months), and long-term exposure (more than 12 months). No exposure type was determined for cross-sectional studies due to design limitations. For consistency, we categorized the comparison groups according to their frequency of exposure. For example, using the definition of current use as using the respective product in past 30 days, we categorized e-cigarette users as non-smoker current vapers, never smoker current vapers, former smoker current vapers, and dual users. Similarly, we established other categories like non-vaper current smokers, never vaper current smokers, former vaper current smokers, non-users, and never users. If a study met the eligibility criteria for meta-analysis, we extracted the relevant sample size and event rates for each comparison groups. Data extraction sheets are presented as Supplementary file Tables S2–S4.

Quality assessment

Two independent reviewers used the different risk of bias assessment tools for quality assessment of individual studies. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion. For non-randomized experimental studies and longitudinal observational studies, we used the Cochrane risk of bias tools – Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool (ROBINS-I)15 and Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies- of Exposure (ROBINS-E) tool16, respectively, and rated the studies as having as ‘low’, ‘moderate’, ‘serious’ and ‘critical’ risk of bias. For cross-sectional, case reports and case series, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool17 except for the studies that involved biomarker-based cross-sectional assessment where we used the BIOCROSS risk of bias tool18. Following the approach of previous research19,20, a study was considered to have a ‘low’, ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ risk of bias if the total score was ≥70%, 50–70%, <50%, respectively, in the JBI critical appraisal tools17 or 13–20, 7–12, and ≤6, respectively, in the BIOCROSS tool18. Additionally, we used the Office of Health assessment and Translation (OHAT) tool21 and the Systematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) tool22 for the cell/in vitro and animal studies, respectively. Studies were considered ‘low’, ‘moderate’, and ‘high’ risk of bias if the majority, half and minority criteria were met respectively23.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta-analyses of mainly human observational studies to compare risk of incidence of respiratory symptoms and prevalence of COPD in non-smoker current vapers and dual users. We excluded any case studies or case series, studies that did not have any clear definition of the exposure received, and studies where outcome was assessed in current vapers instead of non-smoker current vapers. Cell/in vitro and animal studies were also excluded from meta-analysis due to wide heterogeneity between studies. We attempted to obtain missing data from two studies24,25 for inclusion in the meta-analysis but failed to get any response from the authors and eventually excluded these studies from meta-analysis. The detail reasons for exclusion in the meta-analysis, relevant extracted data, and reviewers’ information are provided in Supplementary file Table S4. We used random effects models for meta-analysis according to the Cochrane guidelines and calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI with p-value for binary outcomes26. We considered results statistically significant when p<0.05 or 95% CI did not cross the null value. Heterogeneity in the dataset was measured by τ2 and χ2 tests, and I2 statistic, and we used restricted maximum likelihood (REML)27 to measure heterogeneity in τ2. Heterogeneity in the dataset was determined as low, moderate and high, when the I2 statistic value was <25%, 25–50% and >50%, respectively28. Additionally, we used Doi plot and Luis Furuya Kanamuri (LFK index)29 for identifying small-study effects and publication bias. LFK index value of -1 to 1 was considered as no risk of publication bias, while LFK value of -1 to -2 or 1 to 2 as minor risk of publication bias and LFK value of <-2 or >2 as major risk of publication bias29. Due to the low number of studies (n=2) included in each meta-analysis, we could not conduct sensitivity analysis or subgroup analysis. We used R statistics (version 4.3.0) for the meta-analyses.

For the studies that were not included in meta-analysis, we followed synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM)30 and narrative data synthesis approach31 to present our findings. Studies were grouped as mainly observational studies (i.e. longitudinal observational and cross-sectional studies) and experimental studies (i.e. human, cell/in vitro, and animal studies). Harvest plots30 were used to compare risk of different outcomes between various comparison groups (i.e. non-smoker current vapers, non-users, dual users, non-vaper current smokers). A ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ risk of an outcome was determined when the effect was statistically significant (p<0.05 or 95% CI did not cross the null value), otherwise it was considered as having ‘similar’ risk. As the studies included in the sociodemographic factor-based subgroup analysis did not meet the eligibility criteria for meta-analysis, we used narrative synthesis approach to present our findings with the exception of using harvest plots for demonstrating sex-based subgroup differences.

Certainty assessment

We used Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach32 for assessing certainty of our meta-analysis evidence and the Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) approach33 for evidence that were found mainly from the harvest plots. We avoided GRADE-CERQual assessment if the findings were based on only one study, and the risk of outcome was not assessed in non-smoker current vapers or dual users. For each finding, two independent reviewers conducted their assessment separately and provided an overall certainty of very low, low, moderate, or high. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion between reviewers.

RESULTS

Study selection

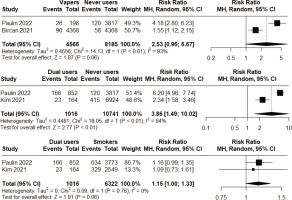

As part of the VECTOR systematic review, we retrieved a total of 8078 articles from the databases. After removing 2953 duplicates, we screened titles and abstract of 5125 articles, of which 562 articles were selected for full text screening. Following removal of 443 articles for various reasons (Figure 1), finally 119 articles24,25,34-36, s37-150 [Supplementary file Material 8, references 37–150] were selected for inclusion in this study. Additionally, from the 427 studies of the McNeill et al.2 review, following removal of 422 studies, we selected 5 studiess151-155 for including in the subgroup analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram showing study selection process for: A) main analysis; and B) from the McNeill et al.2 review for the sociodemographic factor-based subgroup analysis

Study characteristics

Of the 119 studies24,25,34-36, s37-150 included in the main analysis, 26.1% (n=31) evaluated effects of acute exposure, 32.8% (n=39) assessed short-to-medium term exposure and 10.9% (n=13) examined long-term exposure (Table 1). Almost all of the acute exposures were examined by the human non-randomized experimental studies, cell/in vitro and animal experimental studies, whereas all longitudinal observational studies looked into short-to-medium term and long-term exposures. We categorized the outcomes into 8 main categories: respiratory symptoms, COPD, asthma, impact on lung function, lung inflammation and damage, COVID-19 and other respiratory infections, e-cigarette or vaping associated lung injury (EVALI) and other lung conditions, and lung development in utero; of which lung inflammation and damage is the most commonly investigated outcome (n=43; 36.1%). We did not find any study examining passive or secondhand exposure. A total of 18 studies were included in the subgroup analysis, of which 88.2% (n=15) were in sex, and 17.6% (n=3) were in age-based analysis (Table 1). Characteristics of the individual studies are presented in the Supplementary file Material 2 and 3.

Table 1

Summary statistics of included studies published between July 2021 and December 2023 examining respiratory effects of vaping e-cigarettes (N=119)

| Characteristics | Number of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Outcomes/health condition(s) | |

| Respiratory symptoms | 10 (8.4) |

| COPD | 18 (15.1) |

| Asthma | 19 (16.0) |

| Impact on lung function | 14 (11.8) |

| Lung inflammation and damage | 43 (36.1) |

| COVID-19 and other respiratory infections | 23 (19.3) |

| EVALI and other lung conditions | 24 (20.2) |

| Lung development in utero | 7 (5.9) |

| Country | |

| USA | 75 (63.0) |

| Canada | 5 (4.2) |

| European countries | 16 (13.4) |

| Other | 23 (19.3) |

| Type of exposure | |

| Acute | 31 (26.1) |

| Short-to-medium | 39 (32.8) |

| Long-term | 13 (10.9) |

| Study design | |

| Non-randomized experimental | 3 (2.5) |

| Longitudinal observational | 12 (10.1) |

| Cross-sectional | 29 (24.4) |

| Case reports/case series | 24 (20.2) |

| In vitro/cell studies | 14 (11.8) |

| Animal studies | 38 (31.9) |

| Participants (human studies only, N=68) | |

| <100 | 34 (50) |

| 100–1000 | 9 (13.2) |

| 1001–10000 | 7 (10.3) |

| >10000 | 18 (26.5) |

| Age of the participants (years) (human studies only, N=68) | |

| ≤18 | 17 (25) |

| >18 | 58 (85.3) |

| Risk of bias | |

| Low | 62 (52.1) |

| Moderate/some concerns | 31 (26) |

| High/serious/critical | 26 (21.8) |

| Association with tobacco companies | |

| Yes | 5 (4.2) |

| No | 94 (79) |

| Not specified | 20 (16.8) |

| Subgroup analysis (N=17)a | |

| Age | 3 (17.6) |

| Sex | 15 (88.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | 1 (5.9) |

| Sexual orientation | 1 (5.9) |

a Subgroup analysis included studies from both this review (n=12) and the McNeill et al.2 review (n=5). EVALI: e-cigarette or vaping associated lung injury. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Quality assessment

Of the 119 studies, 52.1% (n=63) had low risk of bias (Table 1, Supplementary file Material 4). Of the 26 studies that had high risk of bias, one was a non-randomized experimental study examining effect on lung functions100, another was a longitudinal study examining incidence and prevalence of asthmas44, and others were cell/in vitro and animal studies36, s38,41,42,47,56,59,60,64,73,83,88,101,108,111,118,119,125,128,129,132,138,148,149. Five studies were either funded by or had any association with tobacco companiess47,109,123,138,144, while the association status could not be determined for 20 studiess43,51,53,68,69,74,80,84,85,93,105,114,120,125,126,130,132-134,136.

Respiratory symptoms

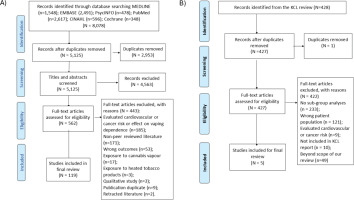

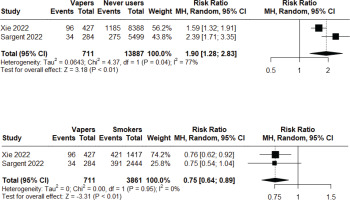

Two longitudinal observational studiess116,143 of low to moderate risk of bias were included in a meta-analysis to assess the incident risk of respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, wheezing, or shortness of breath) following at least short-to-medium term exposure. Non-smoker current vapers had significantly higher incident risk compared to never users (RR=1.90; 95% CI: 1.28–2.83; n=14598), but significantly lower incident risk compared to non-vaper current smokers (RR=0.75; 95% CI: 0.64–0.89; n=4572). Heterogeneity was high (I2=77%) in the first comparison, but low (I2=0%) in the second comparison (Figure 2). Additionally, we found that dual users had significantly higher incidence risk compared to both never users (RR=2.53; 95% CI: 1.44–4.45; n=14800) and non-smoker current vapers (RR=1.26; 95% CI: 1.03–1.55; n=1624), but the risk was not statistically significant when compared with non-vaper current smokers (RR=0.97; 95% CI: 0.84–1.14; n=4774). Heterogeneity was high (I2=94%) in the first comparison, but low (I2=0%, I2=17%, respectively) in the latter two comparisons (Figure 3). Major risk of publication bias was detected in the Doi plots (LFK index 2.98, -2.84, 2.02, 2.49, respectively) for the comparison of: 1) non-smoker current vapers with never users and non-vaper current smokers; and 2) comparison of dual users with never users and non-smoker current vapers indicating small study effects. The comparison between dual users and non-vaper current smokers had minor risk of publication bias (LFK index 1.79) (Supplementary file Material 5).

Figure 2

Meta-analysis comparing incidence of respiratory symptoms among non-smoker current vapers vs never users (top graph) and non-smoker current vapers vs non-vaper current smokers (bottom graph) in observational studies

Figure 3

Meta-analysis comparing incidence of respiratory symptoms among dual users vs never users (top graph), dual users vs non-smoker current vapers (middle graph), and dual users vs non-vaper current smokers (bottom graph) in observational studies

Among the other observational studies that were not included in the meta-analysiss45,49,50,52,86,96,123,137, 2 studiess50,96 detected higher risk of respiratory symptoms in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-users (Figure 4). One of these 2 studies was a longitudinal observational study assessing the incident risk of respiratory symptoms following long-term exposures96. The same study found higher risk in dual users compared to non-userss96, while another study found lower risk in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-vaper current smokerss123. Rest of the studies were too heterogenous in terms of their population and findingss45,49,52,86,137, limiting comparability

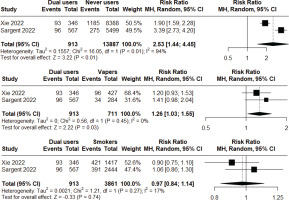

COPD

One longitudinal observational study and two cross-sectional studiess43,81,106 of low risk of bias were included in meta-analyses to compare prevalence of COPD. Non-smoker current vapers have statistically non-significant risk (RR=2.53; 95% CI: 0.96–6.67; n=12751) of prevalence of COPD compared to never users. However, dual users were found to have significantly higher risk (RR=3.86; 95% CI: 1.49–10.02; n=11487) compared to never users, but no statistically significant difference was seen when compared to non-vaper current smokers (RR=1.15; 95% CI: 1.00–1.33; N=7338) (Figure 4). Heterogeneity was high (I2=93–94%) for the first two analyses, but low (I2=0%) for the last one. Major risk of publication bias was detected in the Doi plots (LFK index 2.08, -2.92, -3.76, respectively) for all three meta-analyses (Supplementary file Material 5).

Harvest plots of observational studies24, s54,92,106,142 revealed that the majority of the studies found higher risk of COPD in non-smoker current vapers24, s92,106 and dual users24, s106,142 compared to non-users (Supplementary file Figure 1). Additionally, harvest plots of the experimental studiess60,64,112,113,145,148,150 showed similar findings with all studies except ones148 reporting higher risk of COPD following acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-use (Supplementary file Figure 2). However, all evidence on experimental studies were cell/in vitro or animal based. On the other hand, one observational study found similar incident risk of COPD between non-smoker current vapers and non-vaper current smokers following long-term exposures106 (Supplementary file Figure 1). Similarly, one cellular experimental study detected no statistically significant differences in risk of COPD following acute exposure to e-cigarettes compared to cigarettess64, indicating similar response (Supplementary file Figure 2). The population and findings in other observational studiess37,43,52,58,65,137 were too heterogenous to reach any conclusion.

Asthma

No meta-analysis could be conducted to assess risk of asthma from e-cigarette use. However, harvest plots of observational studies24,25, s85,92,135,141,142 showed that the majority of the studies detected higher risk of asthma or asthma severity in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-userss92,135,141,142, but no significant higher risk in dual users compared to non-users24,25, s85,141 (Supplementary file Figure 1). On the other hand, harvest plots of experimental studies showed that all studies detected higher risk of asthma following acute and short-to-medium term exposure of e-cigarettes compared to non-uses64,89,128,129 (Supplementary file Figure 2). Of the experimental studies, one was a non-randomized human experimental study assessing biomarker-based evidence of increased susceptibility to asthma following acute exposure to e-cigarettess89. Additionally, one of the animal experimental studies found similar risk of asthma following acute exposure to e-cigarettes compared to cigarettess64. The rest of the studies were too heterogenous in population and findingss37,43,44,49,58,65,86,137 to allow for meaningful comparison.

Impact on lung function

We could not conduct any meta-analysis to assess the impact on lung function following e-cigarette exposure. Two animal experimental studies did not find any significant evidence of impairment of lung function (e.g. forced expiratory volume in the first second/forced vital capacity ratio) following acute exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-uses115,144 (Supplementary file Figure 2). On the other hand, although two human non-randomized experimental studies did not find any significant risks89,100, four animal experimental studies reported higher risk of impairment of lung function following short-to-medium term exposures113,119,148,150. Additionally, one animal experimental study found similar risk of impairment of lung function following short-tomedium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to cigarettess144. The rest of the studies were heterogeneous in their studied population and findingss52,55,57,76,81,86.

Lung inflammation and damage

No meta-analysis could be conducted to assess the risk of lung inflammation and damage from e-cigarette use. Harvest plots of observational studiess107,110,122,139,146 showed that all studies except ones146 found higher risk of lung inflammation and damage in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-users (Supplementary file Figure 1). All studies were cross-sectional in study design. Similarly, harvest plots of experimental studies35, s39-42,47,55,56,59,60,63,66,70,73, 75,83,88,89,93,94,97,101,113,115,117,119,121,127,131,132,138,140,144,148,149 showed that all studies except threes47,75,144 found higher risk of lung inflammation and damage following acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-use (Supplementary file Figure 2). Among the experimental studies, two were human non-randomized experimental studiess89,117, and rest of the studies were cell/in vitro and animal studies. Additionally, one observational study reported higher risk in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-vaper current smokerss139 (Supplementary file Figure 1), while two animal experimental studies reported similar risks42,113, one study reported lower risks144, and one study found higher risks55 following acute and short-to-medium term exposure of e-cigarettes compared to cigarettess42,55,113 (Supplementary file Figure 2). Other studies were too heterogenous in their study populations38,57,125.

COVID-19 and other respiratory infections

No meta-analysis was conducted to assess the risk of COVID-19 and other respiratory infections. Among the observational studies found on these outcomes, four studies reported higher risk of COVID-19 or other respiratory infections in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-userss72,78,95,107, while 4 other studies found no such significant risks62,79,109,147 (Supplementary file Figure 1). Two studies in the latter group were longitudinal observational studiess62,147. On the other hand, all experimental studiess42,64,88,108,111,112,118,149 showed higher risk of respiratory infections following acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-use, although all were cell/in vitro and animal studies (Supplementary file Figure 2). Additionally, one observational study found similar risk in dual users compared to non-userss95, while another observational study showed lower risk in non-smoker current vapers compared to non-vaper current smokerss78 (Supplementary file Figure 1). Similarly, one animal experimental study reported similar risk, while another animal study found lower risk following e-cigarette exposure compared to cigarette exposures42,64 (Supplementary file Figure 2). Other studies were heterogenous in their study populations37,65,91 to allow comparison.

EVALI and other lung conditions

Of the five case seriess68,69,82,134,136 and thirteen case reportss48,51,53,61,67,71,74,80,87,99,105,114,126 looking into EVALI, one case seriess68 and five case reportss51,53,61,67,126 reported presence of EVALI in exclusive nicotine vapers, following mostly short-to-medium term exposure. The rest of the cases were mostly dual vapers of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and nicotine or exclusive THC vapers. Additionally, we found three cases of acute eosinophilic pneumonia34,s120,133, one case of diffuse alveolar hemorrhages84, one case of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosiss90, and one case of sarcoidosiss130 among e-cigarette users. No meta-analysis or harvest plots were used to assess the risk of EVALI in nicotine e-cigarette users.

Lung development in utero

We found seven animal experimental studies that reported impaired lung development or lung function in the offsprings exposed to nicotine e-cigarettes in utero36, s46,98,102-104,124 (Supplementary file Figure 2). These changes included reduced lung weight and impaired mucociliary clearance, emphysematous changes, lung fibrosis, respiratory inflammation, and changes in gene expression. Only one animal experimental study compared lung development in utero between exposure to e-cigarettes and cigarettes, and found lower risk of impact following e-cigarette exposures124. We did not conduct any meta-analysis to assess the risk of impaired lung development following e-cigarette exposure in utero.

Sociodemographic factor-based subgroup findings

Supplementary file Material 6 depicts the distribution of studies comparing different respiratory effects based on sex subgroups. As evident, there were inconsistent findings on sex-based differences in COPD and asthma, impact on lung function, and lung development in utero. One longitudinal observational study reported higher risk of asthma in female current vapers compared to male current vaperss135, while another cross-sectional study found lower risk of COPD in female dual users compared to male dual userss81. Similarly, while one animal experimental studys113 reported higher risk of COPD, another animal studys128 found lower risk of asthma in female mice compared to male mice. Additionally, one animal study reported higher risk of impact on lung function in female mice compared to male mice, while another animal study found no such differencess113,148. In case of lung development in utero, one animal study reported higher risk of impaired lung development in female offsprings compared to male offsprings, one animal study found the opposite effect, and two other animal studies found mixed findings36, s46,98,102.

Among the experimental studies examining sex-based differences in lung inflammation and damages113,148,151,154,155, the majority of the studies found no sex-based differencess113,148,151 (Supplementary file Material 6). In case of COVID-19, two animal experimental studiess152,153 found lower risk in females compared to males, while one cross-sectional study reported mixed findingss91. Among the three cross-sectional studies examining age-based differences, one study reported higher odds of prevalence of COPD in older dual users (≥65 years) compared to younger (40–64 years) dual userss81, one study found higher risk of increased asthma severity in older (≥60 years) current vapers compared to younger (18–39 years) current vaperss128, and another study found higher odds of prevalence of COVID-19 in older people compared to younger people (average age of the population was 20.3 ± 1.5 years)s91. The third study also examined race, and sexual orientation-based differences in prevalence of COVID-19 and reported higher risk in non-Hispanic Whites compared to others, and no significant differences between heterosexual and sexual minority peoples91. No meta-analysis could be conducted to assess any sociodemographic factor-based differences for different respiratory outcomes.

Certainty of evidence

Supplementary file Material 7 summarizes the evidence profile on different components of the GRADE and GRADE-CERQual certainty assessment for each individual findings and Table 2 presents the summary of these assessments. Overall, all meta-analysis findings were rated as ‘very low’ to ‘low’ certainty evidence, while harvest plot findings were rated as ‘very low’ to ‘moderate’ certainty evidence. None of the findings was rated as having ‘high’ certainty evidence.

Table 2

GRADE and GRADE-CERQual summary of findings on certainty of the evidence based on the studies included in main analysis and subgroup analysis (N=88)

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted several important findings on the respiratory health impacts of e-cigarette use. First, both meta-analysis and harvest plot findings showed that non-smoker current vapers had significantly higher incident risk of respiratory symptoms compared to never users and non-users, respectively. Nevertheless, the risk level was found to be lower than that seen among non-vaper current smokers. Additionally, dual users were found to have significantly higher incident risk of respiratory symptoms compared to both never users and non-smoker current vapers, and the risk level was similar to that seen among non-vaper current smokers. Although these findings ranged from ‘very low’ to ‘moderate’ certainty evidence, they were consistent with previous reviews3, s156.

Second, although non-smoker current vapers were not found to have any statistically significant increase in the risk of prevalence of COPD compared to never users in meta-analysis, harvest plot findings suggested they had higher risk compared to non-users. The later finding was rated as having ‘moderate’ certainty evidence and matches with previous meta-analyses9, s157. Additionally, evidence from the experimental studies showed higher risk of COPD following both acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-use. The discrepancy between the meta-analysis and harvest plot findings appears to stem from the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis. Both meta-analysis and harvest plot findings demonstrated that dual users had higher risk of prevalence of COPD compared to never users and non-users, respectively, where the harvest plot finding has ‘moderate’ certainty evidence. Moreover, the risk level was found to be similar to that seen among non-vaper current smokers. These findings question the safety of e-cigarette use as a smoking cessation aid and underscore the need for further investigation into the association.

Third, we found ‘moderate’ certainty evidence that non-smoker current vapers had higher risk of asthma or asthma severity compared to non-users. Similarly, experimental study findings revealed that acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes increases risk of asthma compared to non-use. These findings matches with previous reviewss158,159. Although dual users seemed to have no such significant risk, it contradicts a previous meta-analysiss157, hence, this association should be further investigated. Additionally, there was higher risk of impairment of lung function following short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-use (Supplementary file Figure 2). However, no such risk was found following acute exposure, which matches findings from previous reviews2, s160.

Fourth, we found ‘moderate’ certainty evidence that non-smoker current vapers had higher risk of lung inflammation and damage compared to non-users. Similarly, there was substantial number of experimental studies suggesting that both acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes can induce significant lung inflammation and damage compared to non-use, and the risk level was similar to that of cigarettes following short-to-medium term exposure. Although it was ‘low’ certainty evidence, the findings matches previous reviews161.

Fifth, there were inconsistent findings on risk of COVID-19 and respiratory infections among non-smoker current vapers compared to non-users, but higher risk was seen following both acute and short-to-medium term exposure to e-cigarettes compared to non-use in the experimental studies. Hence, more human longitudinal research is needed to further investigate this association.

Sixth, consistent with previous evidences162,163, we found ‘moderate’ certainty evidence that EVALI is mostly associated with cannabis vaping, rather than nicotine vaping. However, future longitudinal observational studies are needed to reach a definitive conclusion. Additionally, animal study findings suggest that exposure to e-cigarettes in utero increases risk of impaired lung development and function in offsprings, which definitely needs to be further investigated though future human research.

Finally, our findings on sex-based subgroup analysis revealed no significant sex differences in the risk of lung inflammation and damage, but lower risk of COVID-19 in females compared to males. As the findings on other sex-based differences were inconsistent and findings on other sociodemographic factor-based subgroup analysis were insufficient to reach any conclusion, further longitudinal investigations are warranted.

We observed several methodological challenges and research gaps in the included studies, which need further attention. For example, several studies defined their population as current vaperss49,65,77,85,100, without clearly distinguishing amongst non-smoker current vapers, former smoker current vapers and dual users. It might be inappropriate and misinformative to the audience to indicate risk of respiratory effects in current vapers, whereas this effect might be from smoking cigarettes rather than e-cigarettes. In addition, while it is important to examine effect of e-cigarette exposure among non-smoker current vapers, it is equally important to understand the magnitude of effects in former smoker current vapers and dual users compared to non-vaper current smokers. There was significant lack of evidence on long-term respiratory effects of e-cigarette use, highlighting the need for prospective longitudinal observational research to assess these effects.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. First, most of our findings were rated as ‘very low’ and ‘low’ certainty evidence with a few ‘moderate’ certainty evidence (Table 2). Hence, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The reasons behind having ‘very low’ and ‘low’ certainty evidence were mainly availability of low number and quality of studies, and lack of enough human evidence. Therefore, it highlights the need for more longitudinal observational research and rigorously designed randomized controlled trails to further investigate our findings. Second, our meta-analysis findings are limited by the number of studies, high heterogeneity in the data, lack of robust estimators, and minor to major risk of publication bias. These limitations present a considerable barrier to the generalizability of our results. To strengthen our synthesis, we complemented the meta-analysis with a SWiM approach and visualized findings using harvest plots. Nevertheless, in respect of previous evidence3, s156,164, it is worth exploring the risk of incidence and prevalence of COPD and respiratory symptoms among different e-cigarette user populations and updating our findings by adding new data from future research. Third, we included studies that were published following the McNeill et al.2 review to avoid duplication with previous reviews2,3. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted alongside theirs. A future umbrella review can be conducted to easily incorporate studies from previous reviews alongside those from our review. Fourth, there are some methodological differences between the McNeill et al.2 review and our review. For example, the McNeill et al.2 review did not include any self-reported data, hence did not report findings on the incidence or prevalence of any respiratory conditions. However, we thought this information were important to understand population trends and included studies with self-reported data in our review. Moreover, the McNeill et al.2 review mostly defined non-use as not smoking or vaping in the past 6 months, and daily or almost daily use as current use. We defined our comparison groups differently to reflect the definition of current use (use in the past 30 days) that was used in the majority of the studies. Hence, these differences should be kept in mind while comparing our findings with the McNeill et al.2 review. Finally, other limitations of this review include the absence of grey literature search, multiple comparisons and outcomes that may inflate positive results, potential residual confounding in included studies, and the inability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, we did not assess the impact of dual vaping of THC and nicotine on respiratory outcomes beyond EVALI. Future research should address these limitations to strengthen the evidence base.

CONCLUSIONS

We found evidence of significant harmful respiratory health effects from use of e-cigarettes such as increased risk of respiratory symptoms, COPD, asthma, impact on lung function, and respiratory inflammation. However, most of our findings were severely limited by having ‘very low’ and ‘low’ certainty evidence, number of studies, and methodological quality. Hence, there is a need for future research to update the evidence and investigate further respiratory risks of e-cigarette exposure by conducting rigorously designed clinical trials and longitudinal studies.