INTRODUCTION

Second-hand tobacco smoke is one of the most widespread air pollutants in indoor environments1. Exposure to it has been linked to several health outcomes, including respiratory asthma, infections of the lower respiratory tract, otitis media and sudden infant death syndrome, as well as ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer in adults1. The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), an international health treaty, promotes smoke-free environments to achieve effective protection from the hazards of secondhand tobacco smoke. Article 8 of the FCTC calls upon Parties to implement measures for protection from exposure to tobacco smoke in public places, including but not limited to indoor workplaces, public transportation, indoor public places, and other public places2. Guidelines for the implementation of Article 8 have been developed further to assist countries in the adoption and implementation of smoke-free measures, as well as in identifying the key elements of their smoke-free legislation3.

Ratification of the WHO FCTC is associated with the accelerated implementation of key demand-reduction measures, including smoke-free laws4,5, with evidence of significant dose-respondent decreases in smoking prevalence and highest-level implementation of these measures6. Since 2004, many countries have adopted complete national smoking bans in public places, which has resulted in benefits to both non-smokers (less second-hand smoke exposure) and smokers (tend to smoke less, have greater cessation success, and experience more confidence in their ability to quit)7. However, only 16% of the world’s population is covered by comprehensive smoke-free laws7. Furthermore, these policies at the national level have only been adopted within the public domain and do not usually apply to private settings, such as homes and cars, where exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke is still common8,9. Nevertheless, some studies indicate that smoke-free legislation has had unexpected effects in promoting private smoke-free settings10,11. It has been hypothesised that public policies affect a variety of psychosocial and behavioural variables12. We hypothesise that the implementation of robust smoke-free legislation in public places will lead to the subsequent cessation of smoking in public places; this will in a second stage lead to changes in psychological mediators (e.g. awareness of the health effects of second-hand tobacco smoke) and in a third stage to behavioural changes, such as the establishment of voluntary tobacco-free policies in private settings.

Little is known on the extent to which smokers implement smoke-free bans within their own private settings. Thus, the objective of this study was to assess existing smoking rules and their correlates in smokers’ private settings, such as homes and cars, in six European countries.

METHODS

Design

This study is part of the European Commission Horizon-2020 funded study entitled European Regulatory Science on Tobacco: Policy implementation to reduce lung diseases (EUREST-PLUSHCO-06-2015; https://eurestplus.eu/), with main objective to monitor and assess the impact of the ratification of the WHO FCTC at the European level, through the implementation of the Tobacco Products Directive (2014/40/EU)13. To achieve this goal, a prospective cohort study of approximately 6000 smokers began using representative samples of smokers in each of the following six European Union (EU) Member States (MS): Germany (n=1003), Greece (n=1000), Hungary (n=1000), Poland (n=1006), Romania (n=1001), and Spain (n=1001).

This cohort survey, the ITC six European countries survey (ITC 6E Survey), is part of the ongoing International Tobacco Control Project Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project (www.itcproject.org/), which aims at tracking and comparing the impact of national-level tobacco policies among representative samples of adult smokers in 29 countries. The methods used in the ITC 6E Survey are explained elsewhere14. Briefly, samples of adult (≥18 years old) current smokers (having smoked >100 cigarettes in their lifetime and having smoked at least once in the past 30 days) were recruited using probability sampling methods, representative of all geographical regions in each EU MS. Eligible households were randomly selected using a random-walk method, and a household was considered eligible if it included at least one eligible smoker. Where available, both one male and one female smoker were selected from each household using the last birthday method15. Baseline data (i.e. Wave 1 of the ITC 6E Survey) were collected over a month, in each EU MS, between June and September 2016. After informed consent was provided, a computer-assisted personal interview was conducted. Participants received remuneration as an incentive for their participation. The study protocol was approved by an ethics committee in each participating country and partnering institutions.

This report is a cross-sectional baseline analysis of data collected from Wave 1 on the degree to which smoking rules are implemented in private indoor settings, namely, in smokers’ homes and in their cars in the presence of children.

Measures

Smoking rules in homes

Rules in homes were ascertained by the question: ‘Which of the following statements best describes smoking inside your home? I mean inside your house or dwelling and not on the balcony, terrace, or other outdoor areas’. The possible answers were: ‘smoking allowed anywhere inside the home’, ‘smoking allowed in some rooms inside the home’, ‘smoking never allowed anywhere inside the home’, and ‘smoking not allowed inside home except under special circumstances’. These possible answers were re-coded as ‘no rules’ (first possible answer), ‘partial ban’ (second and last possible answers), and ‘total ban’ (third possible answer).

Smoking rules in cars

Rules in cars were ascertained with the question: ‘What are the rules about smoking in your car or cars when there are children in the car?’. The possible answers were: ‘smoking never allowed in any car’, ‘smoking allowed sometimes or in some cars’, and ‘smoking allowed in all cars’. These possible answers were re-coded as ‘total ban’, ‘partial ban’ and ‘no rules’, respectively. Answers ‘do not have a car’ or ‘never have children in car’ were excluded from the analyses.

Analysis

We describe the prevalence of different smoking rules (no rules, partial and total smoking ban) in homes and in cars of smokers by EU MS, by several sociodemographic (sex, age, educational level - a country-specific variable standardised and categorised as low, intermediate, and high -, partner’s smoking status, having children) and by smoking characteristics (cigarettes smoked per day - CPD, nicotine dependence measured by the Heaviness of Smoking Index16, and attempts to quit smoking). We also conducted pairwise comparisons of smoking rules (partial vs total ban; no rules vs total ban) according to all independent variables using prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) derived from Poisson regression models with robust variance, adjusting for all independent variables. All the analyses incorporated the weights derived from the complex sampling design. We used Stata v.13 for all analyses.

RESULTS

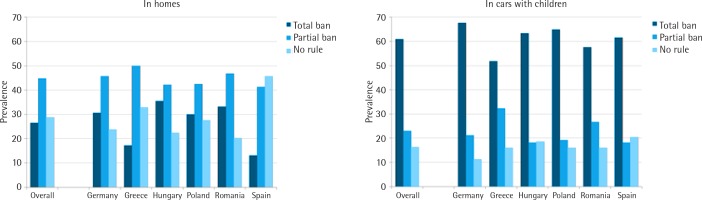

Smoking rules at home

Among all smokers across the six countries, 26.5% reported a total smoking ban in their home, with Hungary having the highest prevalence (35.5%) and Spain the lowest (13.1%); see Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1. On the other hand, 28.8% of smokers across the six countries had no-smoking rules in their homes, varying from 20.2% in Romania to 45.6% in Spain. Overall, the prevalence of a total smoking ban in homes was similar in both sexes, but was significantly lower among participants aged 55 years or older and among those with lower educational level (Table 1). The prevalence of a total smoking ban in homes was higher among smokers with a non-smoker partner and among those with more children. Forty-two per cent of smokers who had children less than one year of age had a total smoking ban in their homes, varying from 11.4% in Spain to 56.6% in Romania (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, there was a higher prevalence of total smoking bans among homes of smokers who reported to smoke less, were least nicotine dependent, and who had ever attempted to quit smoking (Table 1). Information for each EU MS is provided in the Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1

Prevalence of smoking rules in smokers’ homes, according to sociodemographic and smoking characteristics, 2016

| Overall | Total ban | Partial ban | No rules | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %a | n | %b | n | %b | n | %b | pc | |

| Overall | 5967 | 100.0 | 1686 | 26.5 | 2661 | 44.7 | 1620 | 28.8 | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Men | 3155 | 57.4 | 910 | 26.7 | 1328 | 42.6 | 917 | 30.7 | |

| Women | 2812 | 42.6 | 776 | 26.4 | 1333 | 47.6 | 703 | 26.0 | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 18−24 | 507 | 10.1 | 161 | 28.8 | 188 | 36.8 | 158 | 34.4 | |

| 25−39 | 1757 | 31.5 | 553 | 29.6 | 782 | 45.3 | 422 | 25.1 | |

| 40−54 | 1992 | 34.1 | 534 | 25.7 | 957 | 46.5 | 501 | 27.8 | |

| ≥ 55 | 1711 | 24.4 | 438 | 22.9 | 734 | 44.8 | 539 | 32.3 | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Low | 2207 | 37.7 | 563 | 23.5 | 951 | 42.6 | 693 | 33.9 | |

| Intermediate | 3074 | 51.4 | 909 | 28.2 | 1382 | 45.3 | 783 | 26.5 | |

| High | 652 | 10.9 | 206 | 29.7 | 311 | 48.9 | 135 | 21.4 | |

| Smoker partner | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2242 | 58.9 | 569 | 24.6 | 1088 | 47.9 | 585 | 27.5 | |

| No | 1629 | 41.1 | 614 | 35.9 | 737 | 45.8 | 278 | 18.3 | |

| Children | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1958 | 33.6 | 702 | 34.6 | 929 | 47.2 | 327 | 18.2 | |

| No | 4001 | 66.4 | 982 | 22.5 | 1729 | 43.5 | 1290 | 34.0 | |

| Number of children | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 4001 | 66.4 | 982 | 22.5 | 1729 | 43.5 | 1290 | 34.0 | |

| 1 | 1000 | 17.1 | 352 | 34.3 | 493 | 49.5 | 155 | 16.2 | |

| 2 | 709 | 12.1 | 280 | 37.8 | 314 | 43.4 | 115 | 18.8 | |

| ≥3 | 249 | 4.4 | 70 | 27.6 | 122 | 48.3 | 57 | 24.1 | |

| Children’s age (years)d | |||||||||

| <1 | 140 | 7.9 | 59 | 42.0 | 65 | 47.4 | 16 | 10.6 | 0.041 |

| 1−5 | 731 | 38.6 | 287 | 37.4 | 319 | 44.1 | 125 | 18.5 | 0.149 |

| 6−12 | 1029 | 53.2 | 360 | 32.9 | 505 | 48.9 | 164 | 18.2 | 0.247 |

| 13−17 | 760 | 37.4 | 255 | 33.1 | 356 | 46.0 | 149 | 20.9 | 0.119 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 10 | 2063 | 33.2 | 764 | 35.9 | 892 | 43.2 | 407 | 20.9 | |

| 11−20 | 3059 | 52.8 | 771 | 23.5 | 1405 | 45.7 | 883 | 30.8 | |

| 21−30 | 523 | 8.9 | 97 | 16.9 | 224 | 45.2 | 202 | 37.9 | |

| >30 | 314 | 5.1 | 51 | 14.3 | 138 | 44.2 | 125 | 41.5 | |

| Nicotine dependence | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Low | 2341 | 40.0 | 802 | 33.5 | 1021 | 43.7 | 518 | 22.8 | |

| Medium | 2799 | 51.1 | 680 | 22.3 | 1277 | 45.4 | 842 | 32.3 | |

| High | 516 | 9.0 | 74 | 13.0 | 222 | 44.0 | 220 | 43.0 | |

| Attempts to quit smoking | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3223 | 53.4 | 990 | 29.0 | 1439 | 45.3 | 794 | 25.7 | |

| No | 2741 | 46.6 | 695 | 23.6 | 1221 | 44.1 | 825 | 32.3 | |

Table 2

Comparison of smoking rules (partial ban vs total ban; no rules vs total ban) in smokers’ homes, according to independent variables, 2016

| Partial ban vs Total ban | No rules vs Total ban | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | pa | PR | 95% CI | pa | |

| Country | ||||||

| Germany | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Greece | 1.23 | 1.07−1.42 | 0.005 | 1.68 | 1.29−2.19 | <0.001 |

| Hungary | 0.94 | 0.80−1.10 | 0.417 | 1.12 | 0.85−1.47 | 0.422 |

| Poland | 0.99 | 0.85−1.15 | 0.883 | 1.33 | 1.04−1.71 | 0.026 |

| Romania | 1.07 | 0.92−1.24 | 0.394 | 1.27 | 0.97−1.65 | 0.082 |

| Spain | 1.40 | 1.23−1.60 | <0.001 | 2.38 | 1.89−2.98 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Women | 1.09 | 1.04−1.15 | 0.001 | 1.12 | 1.02−1.22 | 0.014 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18−24 | 1.04 | 0.87−1.24 | 0.692 | 1.15 | 0.90−1.47 | 0.259 |

| 25−39 | 1.04 | 0.94−1.15 | 0.445 | 1.01 | 0.88−1.15 | 0.898 |

| 40−54 | 1.04 | 0.95−1.14 | 0.356 | 0.96 | 0.85−1.09 | 0.558 |

| ≥55 | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Low | 1.05 | 0.94−1.18 | 0.370 | 1.51 | 1.20−1.90 | 0.001 |

| Intermediate | 1.00 | 0.90−1.12 | 0.995 | 1.21 | 0.97−1.51 | 0.097 |

| High | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Smoker partner | ||||||

| Yes | 1.18 | 1.10−1.27 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.33−1.68 | <0.001 |

| No | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Children | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| No | 1.19 | 1.10−1.29 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 1.44 −1.86 | <0.001 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | ||||||

| ≤10 | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| 11−20 | 1.22 | 1.12−1.34 | <0.001 | 1.41 | 1.20−1.64 | <0.001 |

| 21−30 | 1.22 | 1.06−1.42 | 0.007 | 1.52 | 1.22−1.90 | <0.001 |

| >30 | 1.18 | 0.94−1.48 | 0.147 | 1.53 | 1.10−2.14 | 0.013 |

| Nicotine dependence | ||||||

| Low | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Medium | 1.03 | 0.94−1.13 | 0.486 | 1.17 | 1.01−1.36 | 0.038 |

| High | 1.15 | 0.96−1.39 | 0.128 | 1.33 | 1.01−1.76 | 0.044 |

| Attempts to quit smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| No | 1.06 | 0.99−1.13 | 0.090 | 1.18 | 1.06 −1.31 | 0.002 |

We further assessed the association of smoking rules in homes (partial vs total ban; no rules vs total ban) with different independent variables, where prevalence ratios >1 indicate less smoking rules in homes (Table 2). Compared to smokers from Germany, the countries where smokers were more likely to have a partial smoking ban or no-smoking rules in their homes were Spain (PR=1.40, 95% CI: 1.23-1.60 for partial vs total smoking ban; PR=2.38, 95% CI: 1.89-2.98 for no-smoking rules vs total smoking ban) and Greece (PR=1.23, 95% CI: 1.07-1.42 for partial vs total smoking ban; PR=1.68, 95% CI: 1.29-2.19 for no-smoking rules vs total smoking ban). The variables significantly associated with not having smoking rules in homes were: female, low educational level, partner who smokes, no children, more CPD, more nicotine dependent, and never attempted to quit smoking (Table 2).

Smoking rules in cars with children

Overall, 60.9% of smokers stated that they had a total smoking ban in their cars when children were present, 22.9% stated having a partial ban, and 16.2% stated having no-smoking rules at all. Smoking rules varied across EU MS, with Greece having the lowest prevalence for cars with a total smoking ban (51.8%) and Germany having the highest prevalence (67.7%); see Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Analyses examining associations with other independent variables showed that cars with total smoking bans were more prevalent among female smokers, and this increased with age and with educational level.

The prevalence of total smoking bans in cars was also higher among smokers with a non-smoker partner, with more children, among those who smoked fewer CPD, with lower nicotine dependence, and with any ever attempt to quit smoking (Table 3). Overall, smokers consuming >30 CPD were the only group with a prevalence of a total smoking ban in cars of less than 50% (Table 3), varying from 32.6% in Greece to 59.0% in Spain. Information by country is provided in the Supplementary Table 3.

Table 3

Prevalence of smoking rules in smokers’ cars with children, according to sociodemographic and smoking characteristics, 2016

| Overall | Total ban | Partial ban | No rules | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %a | n | %b | n | %b | n | %b | pc | |

| Overall | 3885 | 100 | 2409 | 60.9 | 839 | 22.9 | 637 | 16.2 | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Men | 2060 | 57.4 | 1211 | 57.9 | 481 | 24.3 | 368 | 17.8 | |

| Women | 1825 | 42.6 | 1198 | 64.9 | 358 | 20.9 | 269 | 14.2 | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 18−24 | 272 | 10.1 | 151 | 51.7 | 65 | 25.8 | 56 | 22.5 | |

| 25−39 | 1198 | 31.5 | 729 | 61.7 | 259 | 21.9 | 210 | 16.4 | |

| 40−54 | 1408 | 34.1 | 856 | 59.1 | 340 | 25.5 | 212 | 15.4 | |

| ≥ 55 | 1007 | 24.4 | 673 | 66.3 | 175 | 18.5 | 159 | 15.2 | |

| Educational level | 0.013 | ||||||||

| Low | 1268 | 37.7 | 763 | 58.8 | 269 | 22.1 | 236 | 19.1 | |

| Intermediate | 2091 | 51.4 | 1300 | 61.2 | 447 | 22.9 | 344 | 15.9 | |

| High | 504 | 10.9 | 332 | 65.1 | 116 | 24.2 | 56 | 10.7 | |

| Smoker partner | 0.470 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1611 | 58.9 | 993 | 60.9 | 351 | 22.8 | 267 | 16.3 | |

| No | 1196 | 41.1 | 780 | 63.6 | 238 | 21.5 | 178 | 14.9 | |

| Children | 0.354 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1467 | 33.6 | 925 | 62.5 | 317 | 22.4 | 225 | 15.1 | |

| No | 2412 | 66.4 | 1482 | 60.0 | 519 | 23.0 | 411 | 17.0 | |

| Number of children | 0.047 | ||||||||

| 0 | 2412 | 66.4 | 1482 | 60.0 | 519 | 23.0 | 411 | 17.0 | |

| 1 | 761 | 17.1 | 477 | 61.7 | 154 | 21.2 | 130 | 17.1 | |

| 2 | 545 | 12.1 | 361 | 66.6 | 118 | 21.7 | 66 | 11.7 | |

| ≥3 | 161 | 4.4 | 87 | 53.5 | 45 | 29.6 | 29 | 17.0 | |

| Children’s age (years)d | |||||||||

| <1 | 96 | 7.9 | 63 | 59.4 | 18 | 24.7 | 15 | 15.9 | 0.866 |

| 1−5 | 522 | 38.6 | 335 | 63.7 | 110 | 21.6 | 77 | 14.7 | 0.837 |

| 6−12 | 786 | 53.2 | 483 | 61.4 | 191 | 25.2 | 112 | 13.4 | 0.033 |

| 13−17 | 559 | 37.4 | 357 | 64.0 | 115 | 21.0 | 87 | 15.0 | 0.711 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 10 | 1417 | 33.2 | 1040 | 72.2 | 224 | 16.3 | 153 | 11.5 | |

| 11−20 | 1953 | 52.8 | 1130 | 56.2 | 477 | 26.6 | 346 | 17.2 | |

| 21−30 | 321 | 8.9 | 167 | 55.4 | 76 | 22.5 | 78 | 22.1 | |

| >30 | 189 | 5.1 | 70 | 39.5 | 61 | 30.7 | 58 | 29.8 | |

| Nicotine dependence | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Low | 1619 | 40.0 | 1127 | 68.2 | 297 | 19.3 | 195 | 12.5 | |

| Medium | 1727 | 51.1 | 967 | 54.9 | 419 | 26.1 | 341 | 19.0 | |

| High | 312 | 9.0 | 132 | 45.7 | 93 | 28.3 | 87 | 26.0 | |

| Attempts to quit smoking | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2150 | 53.4 | 1409 | 64.5 | 423 | 20.9 | 318 | 14.6 | |

| No | 1734 | 46.6 | 999 | 56.6 | 416 | 25.1 | 319 | 18.3 | |

Further analysis comparing smoking rules in cars (partial vs total ban, and no rules vs total ban) adjusting for potential confounders showed that, compared to Germany, only smokers from Greece were more likely to have a partial smoking ban rather than a total ban (PR=1.67; 95% CI: 1.20-2.34; Table 4). Smokers from all countries, except Hungary, had a higher prevalence of not having smoking rules than having a total smoking ban in cars, compared to Germany. As shown in Table 4, having no-smoking rules in cars was more likely among smokers at younger ages, low educational level, who smoked more CPD, with medium nicotine dependence, and with no attempts to quit smoking ever.

Table 4

Comparison of smoking rules (partial ban vs total ban; no rules vs total ban) in smokers’ cars in presence of children according to independent variables, 2016

| Partial ban vs Total ban | No rules vs Total ban | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | pa | PR | 95% CI | pa | |

| Country | ||||||

| Germany | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Greece | 1.67 | 1.20−2.34 | 0.003 | 1.68 | 1.10−2.59 | 0.018 |

| Hungary | 0.98 | 0.67−1.43 | 0.921 | 1.48 | 0.94−2.35 | 0.093 |

| Poland | 0.98 | 0.67−1.44 | 0.912 | 1.80 | 1.12−2.88 | 0.015 |

| Romania | 1.44 | 0.98−2.11 | 0.061 | 1.86 | 1.18−2.94 | 0.007 |

| Spain | 1.00 | 0.65−1.54 | 0.993 | 2.06 | 1.34−3.16 | 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Women | 0.89 | 0.77−1.03 | 0.110 | 0.87 | 0.73−1.04 | 0.125 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18−24 | 1.65 | 1.07−2.55 | 0.025 | 1.64 | 1.04−2.58 | 0.033 |

| 25−39 | 1.29 | 1.01−1.65 | 0.039 | 1.36 | 1.04−1.77 | 0.024 |

| 40−54 | 1.45 | 1.19−1.76 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 0.96−1.52 | 0.099 |

| ≥55 | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Low | 1.20 | 0.92−1.57 | 0.176 | 1.55 | 1.09−2.20 | 0.014 |

| Intermediate | 1.11 | 0.88−1.41 | 0.381 | 1.22 | 0.87−1.72 | 0.249 |

| High | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Smoker partner | ||||||

| Yes | 1.04 | 0.89−1.23 | 0.606 | 1.10 | 0.88−1.37 | 0.411 |

| No | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Children | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| No | 1.13 | 0.94−1.34 | 0.194 | 1.22 | 0.99−1.50 | 0.061 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | ||||||

| ≤10 | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| 11−20 | 1.74 | 1.33−2.27 | <0.001 | 1.46 | 1.06−1.99 | 0.019 |

| 21−30 | 1.30 | 0.88−1.90 | 0.184 | 1.81 | 1.19−2.75 | 0.005 |

| >30 | 1.45 | 0.85−2.46 | 0.169 | 2.66 | 1.40−5.05 | 0.003 |

| Nicotine dependence | ||||||

| Low | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Medium | 1.01 | 0.79−1.29 | 0.917 | 1.40 | 1.06−1.85 | 0.018 |

| High | 1.47 | 0.92−2.33 | 0.105 | 1.25 | 0.72−2.16 | 0.423 |

| Attempts to quit smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| No | 1.12 | 0.96−1.31 | 0.141 | 1.28 | 1.06−1.54 | 0.009 |

DISCUSSION

More than a quarter of smokers surveyed across six EU MS reported having a total smoking ban in their homes; a similar proportion of smokers had no smoking rules. Prevalence of total smoking ban in homes varied across countries, from 13.1% in Spain to 35.5% in Hungary. These findings are consistent with data from other studies conducted in European countries within the ITC Project17-20 that indicated cross-country differences in the prevalence of smoke-free homes, varying from 13% in Scotland in 2007 to 38.2% in Germany in 2009. The later studies also indicated an increased prevalence of smoke-free homes in European countries over two survey waves17-20.

A different situation was found in cars when children were present where 61% of smokers had a total smoking ban and only 16% had no rules, with less heterogeneity observed across countries, varying from 51.8% in Greece to 67.7% in Germany. Data from other ITC studies conducted between 2007 and 2008 in France, Germany and the Netherlands indicated generally lower support for smoking bans in cars when children are present (41%, 48%, 64%, respectively)21, probably due to the time that has elapsed between these ITC studies and ours. In a brief review that included eight studies examining attitudes of adult smokers to smoking restrictions in cars with children22, the authors found that support for such regulations generally increased with time, for example, from 63%, 45% and 51% of surveyed smokers in New South Wales (Australia) in 1994, 2000 and 2004, respectively, to 96% in New Zealand in 2007-2008 and 87% in South Australia (Australia) in 200822.

It is noteworthy to mention some differences observed in the prevalence of partial smoking rules and no-smoking rules in homes. For example, we observed that the higher the educational level, the higher the prevalence of partial bans in homes and the lower the prevalence of no rules. Also, the trend in the prevalence of the different rules differed by sex, age group, educational level and having children. The prevalence of no-smoking rules among participants who had children was almost half the prevalence of no-smoking rules among those who did not have children; conversely, the prevalence of partial bans was slightly higher among those who had children. In cars, such differences in prevalence are not remarkable, but we still observed some by educational level in a similar way to what we observed in homes. By CPD, the more the CPD smoked the more the prevalence of partial smoking rules and no-smoking rules; but the increase is two-fold for partial rules, whereas it is three-fold for no rules.

In our study, some of the factors that seem to affect smokers’ support for smoke-free regulations in these private settings are: having higher educational level, having children, and having a non-smoker partner. Age seems to have a different effect on the support for smoking regulation in these settings; higher support for smoke-free homes was observed in younger people and higher support for smoke-free cars in older people. Our data also showed that a total smoking ban in homes and cars was more likely among smokers with higher educational level, as shown by others23,24. This possibly indicates that the adoption of voluntary smoke-free rules among smokers follows diffusion of innovations theory (early adopters are those from more advantaged socioeconomic groups)25. Although having children is taken into account in deciding to have both partial and total smoking bans in both settings, we observed that this factor was more important for total smoking bans. This finding has potential implications for the encouragement of smokers with partial smoking bans to move towards total smoking bans in their homes and cars. In addition, having a non-smoker partner was also associated with smoking bans in homes and cars, indicating the importance of social support in encouraging smoke-free environments in private settings. The social system is crucial for the diffusion of smoking bans, because decisions are made not only at the individual but also at the collective and societal level25, thus highlighting the importance of the interaction between the individual and the environment26.

The results show, however, that some improvements are needed to protect non-smokers from second-hand smoke exposure in private settings, especially vulnerable members of the population, such as children. It has been proven that partial smoking does not effectively protect non-smokers from second-hand tobacco smoke due to leaking smoke27-29; furthermore, smoking in this context is still being promoted as a social norm. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate differences among smokers across the six EU MS in the attempt to implement smoking bans in private settings. Cross-country variation might reflect the level of denormalization of smoking in each country. Furthermore, differences may be related to the implementation status of smoke-free legislation, namely Article 8 of the FCTC, within each EU MS. While smoke-free legislation generally does not have wide jurisdiction over private settings, several studies have demonstrated the positive impact of smoke-free legislation on these unregulated places10,11,30-33. Comprehensive population-level policies may increase the prevalence of smoke-free environments in private settings33,34 by promoting awareness of the harmful effects of second-hand smoke exposure and the beneficial effects of reducing such exposure. Among the EU MS participating in our study, Germany and Poland are the countries were the least proportion of the population is protected by smoke-free laws regulating public places (national regulation is absent in Germany, while Poland has few public places where smoking is prohibited by national law)35. When examining the prevalence of total or partial smoking bans by country, no clear pattern in relation to smoke-free environment legislation was observed; therefore, further longitudinal analyses are necessary to better explain the effects of smoke-free regulations and voluntary smoking bans in private settings. Also, studies should take into account the degree to which public regulations are enforced (overall and by country) and its relationship to other issues, such as social conditions that may affect smoking bans in private settings.

Disentangling the relationship and causal pathway between the awareness of second-hand smoke risks, the country-level climate of smoking denormalization, the degree of implementation of smoke-free legislation, and the individual opting for smoke-free homes and cars, are challenging issues that warrant further research. A comprehensive understanding of the factors associated with the voluntary implementation of smoke-free rules in private settings and the mechanism of impact on the population, can contribute to enhancing and tailoring interventions.

This study has some limitations. First, this is a survey conducted among smokers; thus, some information bias on smoking rules is possible due to social desirability and the general antismoking climate, with country variations across EU-MS. These results, therefore, cannot be generalised to all populations, such as non-smokers. Voluntary smoke-free rules in homes and cars are, however, more frequent among non-smokers36-40. Second, survey questions on smoking rules in cars were asked specifically when children were present in the car, indicating that smoking may still occur in the absence of minors in the car. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the analysis precludes any inference about cause-effect relationships between the variables studied. Fourth, the use of self-reported information may introduce a source of bias that can affect the validity of our results. Nevertheless, self-reporting of smoking bans has been shown to have moderate to high correlation with measures of airborne nicotine, with excellent specificity and positive predictive values29. Also, the use of questionnaires is extensive in population studies, because it allows reaching many people at low cost.

On the other hand, the study has many strengths, including a large sample size, the representativeness of the samples of smokers in each country, and the use of a common questionnaire, derived from the expansive ITC Project14. Moreover, the use of six EU MS with diverse geographical and sociodemographic characteristics provided variability in the implementation extent of smoke-free rules in private settings. These EU MS have different smoking prevalence and different stages of the tobacco epidemic (all of them at advanced stages, III or IV of the tobacco epidemic model)41. In addition, these countries share some legislation, such as the EU Tobacco Products Directive, whilst maintaining their own legislation. This study provides a baseline assessment for analysis of prospective data in successive waves of the EUREST-PLUS cohort study that will allow trends to be examined. The current analysis will further facilitate evaluation of changes in voluntary smoke-free rules in private settings, and other smoking-related variables, as a result of changes in legislation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that a quarter of smokers have a voluntary smoking ban at home and almost two-thirds for cars in the presence of children. These figures, however, are far from satisfactory and highlight the need to promote public policies and interventions aimed at increasing the number of smoke-free homes and cars.