INTRODUCTION

Smoking is one of the leading preventable causes of death worldwide and is associated with nearly eight million deaths each year1. Tobacco smoke contains more than 7000 chemicals, including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and heavy metals2. Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the central nervous system, stimulating dopaminergic reward pathways and playing a key role in the development of addiction3. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND) is a widely used and validated scale in both clinical and epidemiological studies for assessing the level of nicotine dependence4.

Insulin resistance is a condition characterized by a reduced biological response to insulin and plays an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases5. The triglyceride–glucose (TyG) index, calculated using fasting triglyceride and glucose levels, is a practical and reliable marker associated with insulin resistance6. In recent years, evidence has suggested that alterations in brain insulin signaling may be related to reward mechanisms through dopaminergic pathways, potentially associated with addictive behaviors. Therefore, new hypotheses have emerged proposing that insulin resistance, similar to nicotine dependence, may also influence addictive behaviors through dopaminergic pathways7,8.

Studies examining the relationship between smoking and insulin resistance generally emphasize that smoking negatively affects insulin sensitivity9-11. Consistent with this perspective, research on the role of insulin signaling in the dopaminergic system suggests that this relationship may involve shared neural pathways rather than a direct causal link7,8. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between nicotine dependence, assessed by the FTND, and insulin resistance, evaluated using the TyG index, among adult exclusive cigarette smokers.

METHODS

Study design and sample selection

This cross-sectional study was conducted between February and June 2025 at the Smoking Cessation Clinic and the Family Medicine Clinic of Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Trabzon Faculty of Medicine (Approval No: 2025/176; Date: February 4, 2025). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The sample size was calculated using the G*Power 3.1 software12 for correlation analysis. Assuming a two-tailed hypothesis, a type I error rate of 5%, an effect size of r=0.50, and a statistical power of 80%, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 66 participants. The selected effect size corresponds to a large effect according to Cohen’s classification and was chosen to ensure sufficient power in the absence of prior population-specific estimates. As the study protocol predefined that multivariable regression analyses would be performed following significant correlations, a larger sample size was recruited to improve the robustness of the analyses and to allow adjustment for potential confounding variables.

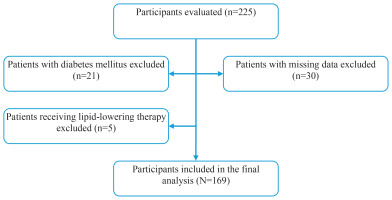

Participants aged 18–80 years who volunteered to participate and reported exclusive combustible cigarette use were included in the study. Individuals using other nicotine products, including e-cigarettes, heated tobacco products, nicotine pouches, or smokeless tobacco, were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (n=21), current use of lipid-lowering therapy (n=5), and missing baseline data (n=30). As a result, 56 individuals were excluded, and 169 participants were included in the final analyses. The participant selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Data collection

The participants’ levels of nicotine dependence were assessed during their outpatient clinic visits using the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence through face-to-face interviews. Demographic information, including age (years) and sex, as well as smoking characteristics such as duration of smoking (years) and the number of cigarettes smoked per day (cigarettes/day), were obtained through structured interviews and verified using outpatient clinic records.

Biochemical data, including fasting glucose (mg/dL) and triglyceride levels (mg/dL), were retrieved from the electronic hospital information system. All laboratory measurements were obtained after an overnight fast and were collected on the same day as the clinical evaluation to ensure temporal consistency. Blood samples were analyzed in the hospital’s central laboratory using standardized automated methods.

Variables and measurements

The dependent variable of the study was the TyG index, an established surrogate marker of insulin resistance. The TyG index was calculated using fasting glucose and triglyceride measurements according to the formula6: TyG = ln ([Triglyceride (mg/dL) × Glucose (mg/dL)]/2).

Independent variables included the FTND score, age, sex, and pack-years.

The FTND consists of six items yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater nicotine dependence4. Although the FTND is formally an ordinal scale, it was treated as a continuous variable in the present study to preserve statistical power and avoid loss of information. All biochemical measurements were obtained from fasting blood samples collected in the morning and analyzed in the hospital laboratory using standardized automated methods. Pack-years were calculated by multiplying the duration of smoking (years) by the number of cigarettes smoked per day (cigarettes/day) and dividing by 20, and were treated as a continuous variable. Age was recorded as a continuous variable, and sex was coded as a categorical variable (male, female).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA)13. The normality of continuous variables was evaluated using skewness–kurtosis values (acceptable range: -1.5 to +1.5) and complemented by visual inspection of histograms and Q–Q plots. Both the TyG index and FTND score showed approximately normal distributions. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were presented as frequency (n) and percentage (%). Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine associations between continuous variables, including FTND score, TyG index, age, and pack-years. Interpretation of correlation coefficients followed conventional thresholds: weak (r=0.10–0.29), moderate (r=0.30–0.49), and strong (r ≥0.50).

Differences in continuous variables between male and female participants were assessed using independent-samples t-tests.

Candidate variables for multivariable linear regression were selected based on their clinical relevance and observed associations in univariable analyses. Variables that showed significant correlations with the TyG index, including age and pack-years, as well as sex, based on their clinical relevance and significant differences in TyG levels in univariable comparisons, were included in the multivariable model together with the FTND score to examine the association between nicotine dependence and insulin resistance. The coefficient of determination (R²) was used to assess the proportion of variance in the TyG index explained by the multivariable regression model. Multicollinearity was examined using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and a VIF <5 was considered acceptable. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p<0.05 was accepted as the threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

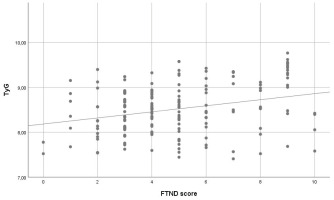

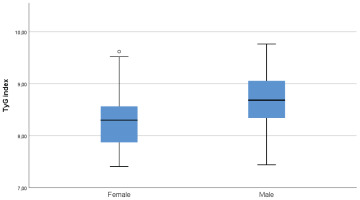

A total of 169 adult exclusive combustible cigarette smokers were included in the analysis. The mean age of the participants was 40.2 ± 12.9 years, and 55.6% were male. The mean TyG index was 8.51 ± 0.56, and the mean FTND score was 4.86 ± 2.32 (Table 1). The TyG index showed significant positive correlations with FTND score (r=0.280; p<0.001), age (r=0.261; p=0.001), and pack-years (r=0.218; p=0.004). FTND score was positively correlated with pack-years (r=0.242; p=0.002), while no significant association was observed between FTND score and age (Table 2). The TyG index was significantly higher in males than in females based on an independent-samples t-test (p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 1

Sociodemographic and biochemical data of adult exclusive combustible cigarette smokers in a cross-sectional study conducted at Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye, 2025 (N=169)

Table 2

Correlations between TyG index, FTND score, and demographic/smoking-related variables among adult exclusive combustible cigarette smokers in a cross-sectional study conducted at Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye, 2025 (N=169)

| Variables | TyG index | FTND score |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | r=0.261 p=0.001 | r=0.025 p=0.751 |

| Pack-years | r=0.218 p=0.004 | r=0.242 p=0.002 |

| FTND score | r=0.280 p<0.001 | - |

Figure 2

Distribution of the triglyceride–glucose (TyG) index, by sex, among adult exclusive combustible cigarette smokers in a cross-sectional study conducted at Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye, 2025 (N=169)

In multivariable linear regression analysis with the TyG index as the dependent variable, higher FTND scores were independently associated with higher TyG levels. In Model 1, which included FTND score only, a significant association was observed between FTND score and the TyG index (β=0.068, SE=0.018; p<0.001). In Model 2, after adjustment for age, sex, and pack-years, FTND score remained significantly associated with the TyG index (β=0.067, SE=0.017; p<0.001). Age (β=0.011, SE=0.004; p=0.002) and male sex (β=0.354, SE=0.078; p<0.001) were also significantly associated with higher TyG levels, whereas pack-years showed no significant association (p=0.703). No evidence of multicollinearity was observed (all VIF values <5) (Table 3). The association between FTND score and the TyG index is shown in Figure 3.

Table 3

Multivariable linear regression analysis of factors associated with the TyG index among adult exclusive combustible cigarette smokers in a cross-sectional study conducted at Trabzon Kanuni Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye, 2025 (N=169)

[i] Model 1: FTND score only. Model 2: FTND score, age, sex, and pack-years included. β: unstandardized regression coefficient. SE: standard error. Model 1: F=14.226, p<0.001; R²=0.078. Model 2: F=12.922, p<0.001; R²=0.221. TyG: triglyceride–glucose index; FTND: Fagerström test for nicotine dependence.

DISCUSSION

This study is novel as it examined the association between insulin resistance, assessed by the TyG index, and nicotine dependence, measured by the FTND. Our findings showed that higher TyG index values were independently associated with higher FTND scores, as well as with older age and male sex. In addition, the FTND score was positively correlated with both the TyG index and cumulative smoking exposure measured by pack-years. Taken together, these findings indicate that insulin resistance is associated with nicotine dependence beyond smoking intensity alone; however, given the cross-sectional design, no causal or directional inferences can be drawn.

Our findings are consistent with the existing literature. Previous studies have shown that cigarette smoking is associated with reduced insulin sensitivity, impaired glucose metabolism, and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes14-16. Studies using the TyG index have also reported significant associations between smoking status and TyG levels16,17. The positive correlation observed in our study between FTND score and the TyG index is in line with these reports. However, human studies directly examining the association between nicotine dependence and insulin resistance remain limited. In this context, our results are consistent with experimental findings by Richardson et al.8 who reported enhanced nicotine reward in insulin-resistant animal models. Taken together, these findings suggest a potential link between insulin resistance and nicotine dependence, while the underlying mechanisms and directionality of this association require further investigation.

In the present study, the TyG index was higher in males than in females, indicating a sex-related difference in insulin resistance. Similar findings have been reported by Jeong et al.17 who observed higher TyG levels in men. This difference may reflect underlying biological and behavioral factors, including hormonal influences and sex-specific patterns of visceral adiposity, as suggested in previous studies5.

The mechanisms underlying the association between insulin resistance and nicotine dependence have not been fully elucidated. Previous studies have suggested several biological pathways that may be involved in this relationship. Cigarette smoking has been associated with reduced insulin sensitivity through processes such as chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, visceral adiposity, and endothelial dysfunction17. In addition, experimental studies have indicated that nicotine exposure may interfere with insulin signaling pathways at the cellular level18,19. Insulin has also been shown to modulate dopaminergic reward pathways, and impaired insulin signaling may influence reward-related responses20,21. In line with this, Richardson et al.8 reported enhanced nicotine reward in insulin-resistant animal models. Taken together, these findings provide biological plausibility for the observed association, while emphasizing the need for further research to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Strengths and limitations

This study adds to the limited number of human investigations evaluating the association between insulin resistance, assessed by the TyG index, and nicotine dependence, measured by the FTND. The sample size exceeded the minimum required, as determined by a priori power analysis, allowing for more robust estimates. Nicotine dependence was assessed using the validated FTND scale, and insulin resistance was evaluated using the TyG index, which has been increasingly applied in epidemiological research. In addition, relevant confounders, including age, sex, and cumulative smoking exposure (pack-years), were considered in the analyses, thereby strengthening the robustness of the findings.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes any causal or directional inferences. Second, the study was conducted at a single center and included volunteers attending an outpatient clinic, which may limit generalizability and introduce volunteer bias, as participants who agreed to take part could differ systematically from those who declined (e.g. in motivation or health awareness). Third, smoking-related variables were self-reported, which may have resulted in misclassification bias. In addition, insulin resistance was estimated using the TyG index rather than direct measures. Furthermore, potential confounding factors, including body mass index, physical activity, dietary habits, and socioeconomic status, were not considered in the analyses; therefore, residual confounding cannot be excluded. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings demonstrate that higher TyG index values were independently associated with greater nicotine dependence, as well as with older age and male sex. These results suggest a potential link between insulin resistance and nicotine dependence. However, given the cross-sectional design of the study, causal or directional inferences cannot be drawn. Larger, prospective studies are warranted to further clarify the direction and clinical relevance of this relationship.